I recently read a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM): “Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease.” This review is one of the latest making the case that when you eat (and don’t eat) can have a profound impact on your health. But before looking into this study (we’ll do that next week), we need a framework to put it into context.

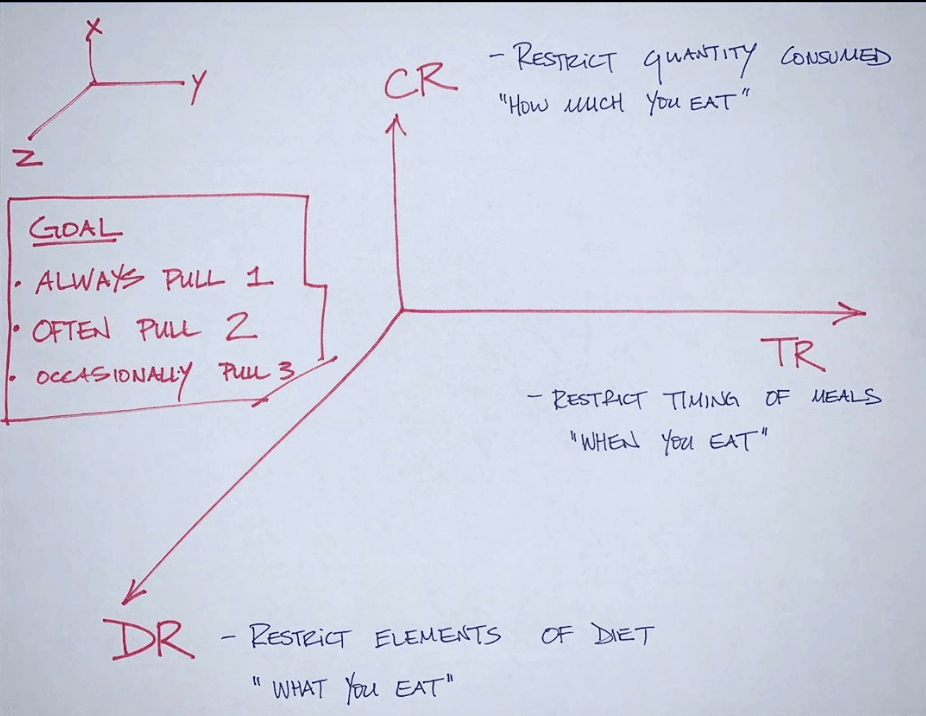

Nutrition is such a loaded topic—almost a religious or political one—so I’m always looking for ways to explain it that are as free from that baggage as possible. So far (and this is constantly evolving, so look for this to get better over time) the framework I use to explain eating is based on modifying three parameters or “pulling 3 levers” in various combinations. A few months ago I posted a short video explaining this way to think about nutrition. It comes down to three forms of restriction. Whether it’s what you eat or don’t eat (i.e., dietary restriction or DR), how much you eat (i.e., caloric restriction or CR), or when you eat and don’t eat (i.e., time restriction or TR), virtually all of the dietary schemes you can think of can be distilled into these three elements in some combination (Figure). Figure. My nutritional framework.

Figure. My nutritional framework.

Of the three levers, TR (often, though in my opinion misleadingly, called “intermittent fasting”) possibly contains the simplest dietary prescription: limit your eating to a window of X hours. For example, “Only eat between noon and 8 pm each day.” That’s it. Most people, out of the gate, are already doing something like a 10/14 TRF schedule, even without a modicum of effort (i.e., not eating for 10 hours; eating within a 14-hour window). From here, it’s pretty easy to get to 12/12 (e.g., only eat between 8 am and 8 pm). Then 14/10, and soon enough 16/8. Before you know it, you’ll be amazed by how easy 18/6 feels (e.g., only eat between 1 pm and 7 pm).

I began experimenting with TRF in earnest in late 2013 and by the end of 2014, I had spent 6 months doing a 22/2 regimen every single day (which works out to basically one meal per day, grazed on over 2 hours). I’ll save the details of that for another time, but the metabolic flexibility I experienced was certainly on par with what I had experienced during my longer journey in nutritional ketosis. For example, though I was only eating one (large) meal per day at dinner, I worked up to doing a 6-hour very tough bike ride on nothing but water in the first half of the day.

Compare this to the thought, planning, and education—for the patient and/or provider—that goes into CR and DR with daily calorie-counting and question(s) around “Is it paleo / keto / vegan / sugar-free?” respectively.

One thing is for certain: if you want to be sick, don’t do any of these things. Eat as much as you want (no CR), of anything you want (no DR), whenever you want (no TR). This is called the “standard American diet.” The further you can get away from this pattern of eating, the better. As I say in the video, always pull one of the levers; often pull two; sometimes pull all three.

Next week we’ll take a closer look at one of these levers, time restriction, and the recent review on it in the NEJM.

Become a premium member

MEMBERSHIP INCLUDES

- Exclusive Ask Me Anything episodes

- Best in class podcast Show Notes

- Premium Articles on longevity

- Full access to The Qualys podcast

- Quarterly Podcast Summary episodes

Related Content

Podcast Episode

Insulin resistance masterclass: The full body impact of metabolic dysfunction and prevention, diagnosis, and treatment

Disclaimer: This blog is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute the practice of medicine, nursing or other professional health care services, including the giving of medical advice, and no doctor/patient relationship is formed. The use of information on this blog or materials linked from this blog is at the user’s own risk. The content of this blog is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Users should not disregard, or delay in obtaining, medical advice for any medical condition they may have, and should seek the assistance of their health care professionals for any such conditions.