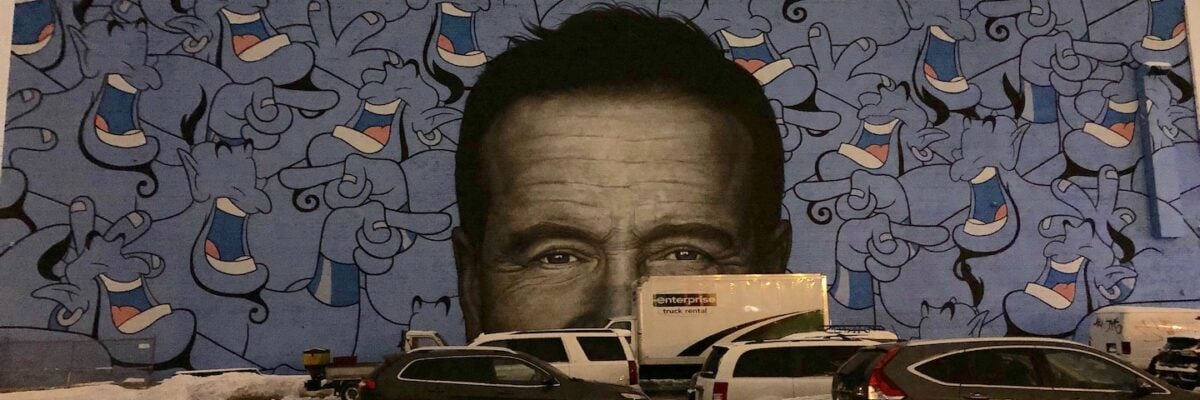

This Tuesday marks the tragic anniversary of the death of Robin Williams. On August 11, 2014, Williams killed himself at his home in California. I still remember the exact intersection I was stopped at when my phone rang. I saw a friend’s name pop up on the screen of my car and thought, “Hmm, I haven’t heard from her in a few months. I wonder what’s up.” About a year earlier she and I had bonded over our shared obsession with much of Robin’s work and now of course she was calling to commiserate the loss of someone neither of us knew personally, but both of us felt a connection to.

Want more content like this? Check out our interviews with Kristin Neff on the power of self-compassion and Esther Perel on the effects of trauma.

On one level—right or wrong—we’ve come to accept such death from “tormented souls,” but most observers of Williams’s work, or of his life outside of work, would hardly think of him in those terms. (Some of my favorite Robin Williams improvisational mastery was his mock Tour de France commentary, his other superfan moments at cycling events, and riffs like this.) On another level, many of us react to these tragedies with anger.

Whenever there’s a suicide in the news, it’s accompanied by pundits explaining that taking your own life is a cowardly act. Not only is it the antithesis of bravery, these people tell you, but it’s also horribly selfish, especially if you have children. Ten days after Williams died, Henry Rollins wrote in his LA Weekly column that he could not understand how any parent would kill themselves—Robin was the father of three children—and regarded anyone who took their own life with disdain. “How in the hell could you possibly do that to your children?” Rollins asked.

Believing that suicide is an act of cowardice is not unique. It’s an understandable feeling if you haven’t experienced the sort of pain that leads to suicidal thoughts. Every year in the U.S., tens of millions of people think about suicide and tens of thousands carry out the act. But the majority of adults, approximately 9-in-10, go through life without ever thinking about killing themselves. I imagine it’s difficult for these people to feel empathy for someone who is suicidal. When people try to put themselves in the shoes of someone who is suicidal, they often think that person performs some calculation of personal happiness and pain without accounting for the friends and family they’ll leave behind. That may seem cowardly, but it’s also a completely inaccurate description of what most suicidal people are thinking.

Deaths of despair—mortality from drug overdoses, alcoholic liver disease, and suicide—are on the rise, increasing by 400%, 41%, and 38%, respectively, between 1999 and 2017. The social isolation, economic stress, and hopelessness related to the COVID-19 pandemic may be making matters even worse. A recent report by the CDC suggested that upward trends in excess deaths associated with COVID-19 may include deaths of despair.

After writing his article, Rollins was flooded with angry letters for several days. He read all of them and quickly realized he had a lot to learn about the issue. “I cannot defend the views I expressed,” Rollins wrote in a follow-up article. “I have no love for a fixed position on most things. I am always eager to learn something.”

Perhaps the main reason why Rollins had disdain for people that killed themselves is Rollins himself battled depression all his life, according to his blog post. Maybe he believed he could empathize with someone struggling with severe depression. But after reading the letters he received, many of them discussing severe depression, it looked like Rollins began to appreciate his lack of understanding. “What has perhaps kept me from seeing things differently about severe depression is that I am sure I don’t have it,” Rollins wrote.

I think it’s important to acknowledge that we may not truly understand what other people are going through, especially from a mental health perspective. It’s a lot easier to try and walk in someone else’s shoes than to try and put your head inside someone else’s brain. It was commendable for Rollins to apologize and show compassion to the people he hurt with his words. Suicide is an issue ripe for the five stages of grief. It’s probably all too common to be angry at someone close to you that took their own life and it’s also something that you may never fully understand and accept.

There’s often more to the story than we think we know. In May of 2014, Williams was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. An autopsy later revealed he actually had Lewy body dementia, a progressive disease that leads to a decline in thinking, reasoning, and independent function. His widow, Susan, said depression was just one of many symptoms he was dealing with. In 2016, Susan shared her story in Neurology hoping to help neurologists better understand their patients.

One of Robin Williams’s closest friends, Bobcat Goldthwait, told Williams’s son after his father’s death, “One of the biggest stars in the world died, and on the same day, your dad died.”

– Peter