If you know anything about me, you probably know how much I love Topo Chico sparkling water. I offer it to anyone I come into contact with, and it’s a staple in my household. I drink it almost every day. Sometimes even a couple of bottles. I might as well bathe in the stuff. So you can imagine how my ears perked up after hearing about (and then reading) the recent Consumer Reports piece that discussed per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) test results from 47 bottled waters (including some flat but mostly sparkling). Given my daily consumption habits, I had one question:

How dangerous is it to drink “normal doses” of, say, 1 to 2 bottles of Topo Chico per day?

Let’s be clear: it’s hard, if not impossible, to answer this type of question with such data. I will discuss below what I take into consideration—what we know–and how to make sense of the conflicting information from varying toxicity guidelines. My thinking process with respect to how to regulate my sparkling water consumption is not a precise science by any means. It requires some inductive reasoning. But this is often the case with limited information. Consider this a mini-case study.

Let’s take a step back and talk about what acronyms like PFAS, PFOA and PFOS stand for and why concluding what is “safe” and “not safe” is a difficult task.

PFAS are a synthetic class of chemicals that include perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). They have been used for industrial purposes in the US since the 1940s. Even though their manufacture has been phased out in the US, they are still present in many imported products. We also know that they remain in the body for a long time (they have a half-life of approximately 4 years). If you ever saw the movie Dark Waters, you saw what a massive infusion of PFAS, specifically PFOA, did to a community of unsuspecting people. Absolutely horrible. But it’s not clear what much, much, much smaller doses mean.

PFOA, also called C8, is an industrial surfactant that is used to manufacture many products such as carpeting and textiles. One study found that there is a “more probable than not” association between PFOA and 6 ailments: kidney cancer, testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, hypercholesterolemia, and pregnancy-induced hypertension. But there was a small sample size, many findings were not statistically significant, and there are epidemiologic confounders potentially not accounted for. (For a little primer on the topic of confounders, please refer back to Part IV of our treatise on understanding science, Studying Studies.)

PFOS is a toxin used in stain repellents like Scotchgard. Higher levels have been associated with preeclampsia, thyroid hormone changes, and high cholesterol. In 2009, the Stockholm Convention decided it had seen enough, and moved to include the compound on a list of persistent organic pollutants that should be restricted in production.

Let’s be clear. There is enough evidence to say that ingesting some amount of PFAS is bad news: the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has it listed as a contaminant of emerging concern (CAC). But how much is too much? Even if there are detectable amounts of PFAS (measured in parts-per-trillion, or ppt) in our preferred bottled waters, does that mean we shouldn’t drink them? And in what quantities are they safe?

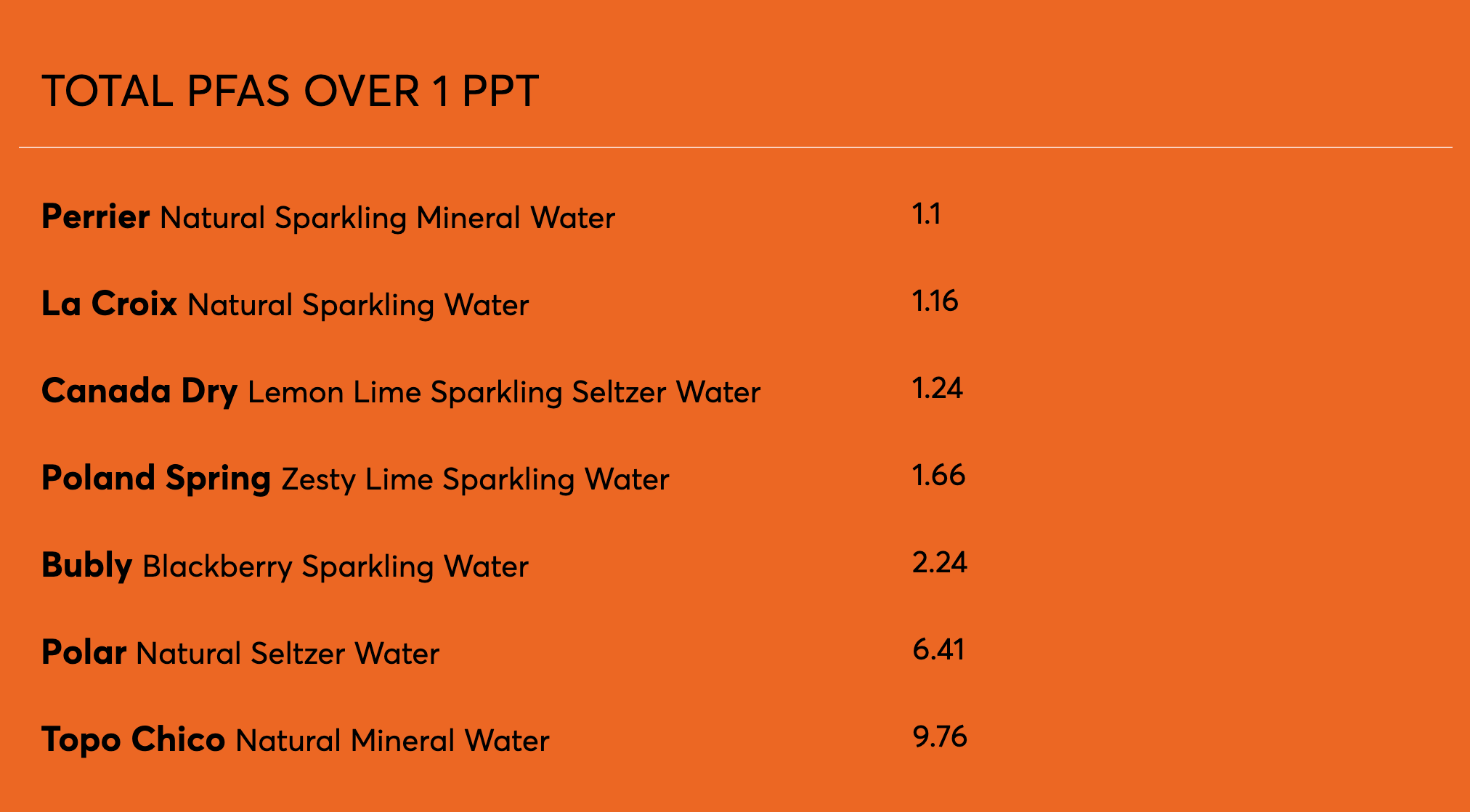

There are no federal standards for levels of PFOA and PFOS in drinking water. The EPA has issued health advisories but not regulations, per se. It says that the combined amounts for these two compounds should be below 70 ppt, but other agencies like the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) submitted regulatory guidelines at far lower levels (3 ppt for PFOA and 2 ppt for PFOS) than the EPA’s limit. Separate guidelines are issued by a few states that have set their own more stringent limits that range from 12 to 20 ppt. The International Bottled Water Association (IBWA) holds that bottled water should have PFAS levels below 5 ppt for any single compound and 10 ppt for more than one. The Table below provides a list of carbonated water products tested by Consumer Reports in which they detected total PFAS over 1 ppt.

Table. A list of total PFAS (PPT units) in carbonated bottled water. (source: consumerreports.org)

So where does this leave my Topo Chico and me? Well, the amount of PFAS in Topo Chico is well below the 70 ppt from the EPA health advisory for maximum amounts in drinking and also below the more stringent state standards of 12-20 ppt. However, it is almost twice the amount of the IBWA standard of 5 ppt.

With respect to the quality of evidence, many studies that have been done suggest an association between PFAS and human illness but, as noted above, much of the data is not statistically significant or it is based on observational data from small, non-representative populations. Nonetheless, because PFAS remains in the body for very long periods of time and because there is reasonable evidence that exposure is dangerous, I can’t just dismiss the finding because I don’t want it to be true. However, in the absence of a “maximum safe level” how shall I interpret the finding of 9.76 ppt for Topo? This is a classic signal-to-noise problem. Is there a chance drinking Topo Chico causes cancer or kidney disease? Sure, just like there is a chance that drinking tap water or using a cell phone causes cancer. But would the magnitude of that insult even remotely approximate that of, say, cigarettes on lung cancer? Not even close. Why? Because we should have seen it by now, just as it was seen in Parkesburg, West Virginia when DuPont was dumping C8 into water and landfills like it was their job. In this sense, epidemiology is actually at its most helpful when it finds a no- to low-signal, as in this case. Given how long Topo Chico has been around and the ubiquity of it, should there be any negative effect from its “normal” consumption, it is likely to be very, very small.

But in the final analysis, at least for me, the precautionary principle, coupled with the asymmetry of being wrong, would suggest it wise to err on the side of caution and cut down on my consumption to a few bottles a week (rather than multiple bottles each day). Am I going to throw out my current stockpile of Topo Chico? No, but I will diversify my consumption with another sparkling beverage (I already have a leading candidate).

The Consumer Reports article did note that Topo Chico (now owned by Coca-Cola) said it would “continue to make improvements to prepare for more stringent standards in the future.” I am hopeful this happens. But until then, a modicum of caution is warranted. The dose always makes the poison, so I’ll reduce my dose until further notice. (And if you’re reading this over at Coca-Cola, please hurry up and clean up the world’s finest sparkling water!)

– Peter