In this episode, John Barry, historian and author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, describes what happened with the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, including where it likely originated, how and why it spread, and what may have accounted for the occurrence of three separate waves of the virus, each with different rates of infection and mortality. While the current coronavirus pandemic pales in comparison to the devastation of the Spanish flu, John highlights a number of parallels that can be drawn and lessons to be learned and applied going forward.

Subscribe on: APPLE PODCASTS | RSS | GOOGLE | OVERCAST | STITCHER

We discuss:

- What got John interested in the Spanish flu and led to him writing his book? [2:45];

- Historical account of the 1918 Spanish flu—origin, the first wave in the summer of 1918, the death rate, and how it compared to other pandemics [10:30];

- Evidence that second wave in the fall of 1918 was a mutation of the same virus, and the immunity immunity protection for those exposed to the first wave [18:00];

- What impact did World War 1 have on the spread and the propagation of a “second wave”? [21:45];

- How the government’s response may have impacted the death toll [26:15];

- Pathology of the Spanish flu, symptoms, time course, transmissibility, mortality, and how it compares to COVID-19 [29:30];

- The deadly second wave—The story of Philadelphia and a government and media in cahoots to downplay the truth [35:50];

- What role did social distancing and prior exposure to the first wave play in the differing mortality rates city to city? [44:45];

- The importance of being truthful with the public—Is honesty the key to reducing fear and panic to bring a community together and combat the socially-isolating nature of pandemic? [46:15];

- Third wave of Spanish flu in the spring of 1919 [51:30];

- Global impact of Spanish flu, a high mortality in the younger population, and why India hit so much harder than other countries [55:15];

- What happened to the economy and the mental psyche of the public in the years following the pandemic? [59:20];

- Comparing the 2009 H1N1 virus to Spanish flu [1:02:10];

- Comparing SARS-CoV-2 to the Spanish flu [1:04:20];

- What are John’s thoughts on how our government and leaders have handled the current pandemic? [1:08:00];

- Sweden’s herd immunity approach, and understanding case mortality rate vs. infection mortality rate [1:10:40];

- What are some important lessons that we can apply going forward? [1:13:00];

- Does John think we will be better prepared for this in the future? [1:16:00]; and

- More.

Show Notes

What got John interested in the Spanish flu and led to him writing his book? [2:45]

- Steve Rosenberg (Peter’s mentor) and John Barry co-authored one of Peter’s favorite books, The Transformed Cell

- In 2004, John wrote The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History

- John mentioned that the book was a grueling process that he frequently second-guessed

- But John says the work and life of Oswald Avery, who discovered that DNA carried the genetic code, inspired John to push through after learning about the hardship that Avery went through

Historical account of the 1918 Spanish flu—origin, the first wave in the summer of 1918, the death rate, and how it compared to other pandemics [10:30]

- John points out that he thinks this is NOT a swine flu (which is a common misconception)

- The 1918 pandemic is a respiratory virus that jumps from animals to people (We don’t know what animal)

- The pandemic killed between 50-100 million people

- Adjusting for population that is 220-440 million people today

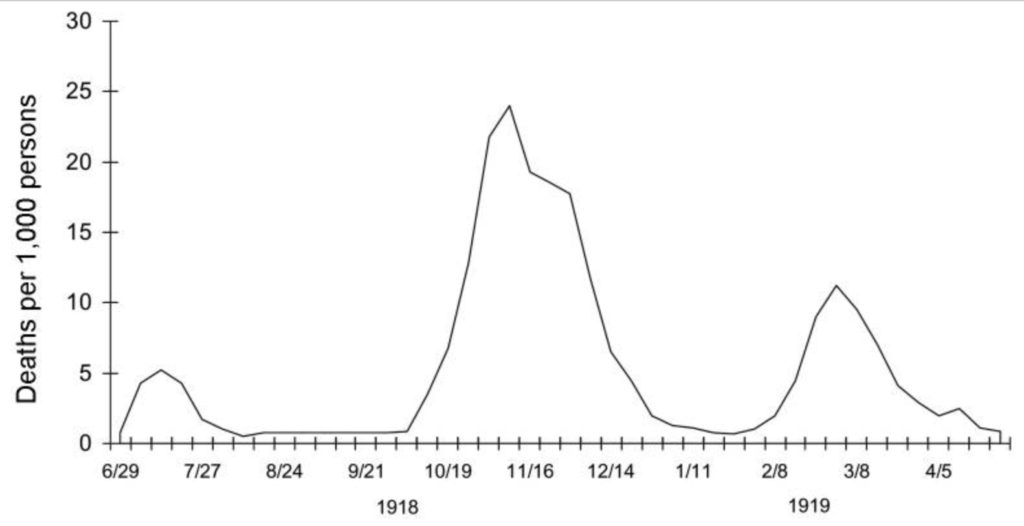

Three waves

- It had a mild/spotty first wave in the spring of 1918 and did not spread worldwide

- The second wave killed ⅔ of those people in about 14 weeks from late September through December 1918

- A third wave hit in February 1919 and lasted through the spring of 1919

Figure 1. Three pandemic waves: weekly combined influenza and pneumonia mortality, United Kingdom, 1918–1919 Image credit: (Taubenberger and Morens, 2006)

Origination

- Haskell County, Kansas was where the first report of a lethal influenza happened

- John originally believed this was where the origin of the virus occurred

- However, more evidence now points to China as to a more likely location of origination

In context against the worst pandemics

- In terms of proportion of the population who were killed, the bubonic plague of the 14th century is the deadliest pandemic

- The Spanish flu killed the most people in TOTAL

Evidence that second wave in the fall of 1918 was a mutation of the same virus, and the immunity immunity protection for those exposed to the first wave [18:00]

John says the evidence is “overwhelming” that the second wave was the same virus and not something different

Evidence includes:

- The deaths in the first wave had a similar demographic as the deaths in the second wave — both had an average age of about 28 years old which is super rare for it to be that young

- Exposure to the first wave was very protective against the second wave — it provided between 59% and 89% protection against the illness

- Scientist have now gotten a DNA sequence of the virus from the spring of 1918 and compared it to the virus DNA sequence of the fall of 1918 and confirmed it’s the same

Figure 2. “U-” and “W-” shaped combined influenza and pneumonia mortality, by age at death, per 100,000 persons in each age group, United States, 1911–1918. Influenza- and pneumonia-specific death rates are plotted for the interpandemic years 1911–1917 (dashed line) and for the pandemic year 1918 (solid line) Image credit: (Taubenberger and Morens, 2006)

What impact did World War 1 have on the spread and the propagation of a “second wave”? [21:45]

How does a virus spread in 1918 when travel was so much harder than it is today?

- For example, there were not airplanes, you needed a ship to cross the ocean

- Despite this, it obviously spread easily

- This video shows a temporal view of where infections popped up over time and “it’s kind of amazing how quickly that second wave grows.”

“You don’t need steam power to move a pandemic in the 1600s… influenza managed to cross the Atlantic ocean and devastate Virginia and Massachusetts, not to mention the Native American population.”

Books mentioned on this topic:

- Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies

- Natural History of Infectious Disease (“I highly recommend to everyone” says John)

What impact did World War 1 have on the spread and the propagation of a “second wave”?

“I think the war accelerated the spread, but I don’t think it’s responsible for the spread. It just happened a little bit faster.”

How the government’s response may have impacted the death toll [26:15]

- John says the fear and chaos created by the way the government handled this situation was a major factor in the high death toll

- The government was very sensitive about controlling the narrative during the first world war which was going on at the time

- It was “determined to control the thought of Americans”

- There was a law — The Sedition Act of 1918 — that made it punishable by 20 years in jail

- The government was going to minimize anything that might depress the American public because they fear that would affect the war effort

- The idea was to keep up morale

- And the architect of that propaganda committee said, “truth and falsehood are arbitrary terms … all that mattered was the impact of what of you are saying”

Pathology of the Spanish flu, symptoms, time course, transmissibility, mortality, and how it compares to COVID-19 [29:30]

- In the western world, the case mortality was about 2%

- The mortality was higher in the less developed world mostly because the west had been exposed to the milder first wave which provided immunity to many

- The 1918 virus, like coronavirus, but unlike most influenza viruses, could bind to cells in the upper respiratory tract which made it easily transmissible

- Additionally, it could also bind directly to cells deep in the lung which meant you were starting out essentially with viral pneumonia

Other symptoms:

- people are so turning dark blue from lack of oxygen

- Nose bleeds were common

- Could also bleed from mouth, eyes, and ear

- Unlike most influenza viruses, the 1918 virus could pretty much attack any organ

While this was happening, the public was being told that this was a normal flu virus and there’s nothing to be concerned about

- But it was clear to the people that this was not normal like other flu viruses

- John says when people feel they are being lied to, society starts to fray

“What it means is you stop trusting anything that you’re being told by anyone in authority. I think society is based on trust. When trust evaporates, society begins to fray.”

A very young demographic dying of this

- It was killing people in their 20s and 30s

- Which is very atypical of the flu which normally kills the elderly and immunocompromised

- But the peak age was 28 … suggesting that the stronger your immune system, the worse off you were

- COVID-19 patients are getting hit in the same way in terms of it being an Acute respiratory distress syndrome ⇒ the virus when it was in the lung, the immune system attacked it with everything it had

However…

- With the 1918 flu pandemic, the majority of people died of secondary bacterial pneumonia and much less from the virus itself

- Some say only 5% of the people died directly because the virus

- John says that is mistaken and he estimates about 30-40% died directly from the virus (and the other 60-70% died from secondary bacterial pneumonia)

*Total US deaths from Spanish flu was roughly ~650,000 deaths (after all 3 waves hit)

The deadly second wave—The story of Philadelphia and a government and media in cahoots to downplay the truth [35:50]

September 28th of 1918 was the Liberty Loan Parade

- It was when the government put on a parade for the public as a campaign to raise money for the war effort

- In Philadelphia, the 2nd wave of the virus had already established itself and the medical community was unanimous that the parade should be cancelled

- However, the media, the government, and even the local public health commissioner were in cahoots to kill off any reports that the parade should be cancelled in an attempt to boost “morale” in the public that they didn’t need to be afraid

- Like clockwork, within 72 hours the influenza had exploded in Philadelphia killing 4,500 people in 3 weeks

- The press was complicit in this as well, says John

- Even as schools were being closed, public gathering being banned, etc. the local papers were saying this is “not a public health measure” and that “You have no cause for alarm”

- Yet, people and family members were dying all around them

“That contributed to the breakdown of society and to the fear and the terror when you can’t believe anything you’re being told.”

What role did social distancing and prior exposure to the first wave play in the differing mortality rates city to city? [44:45]

Social distancing

- St. Louis took part in some aggressive measure of social distancing

- They had a much more “benign” experience compared to other cities

- However, it’s unclear as to how much that contributed to their experience

- Because New York (and Chicago), on the other hand, did almost no restrictions and they had a relatively benign experience as well

- But that can be explained by the fact that NY and Chicago both were exposed to the first wave of the virus offering immunity to much of the communities

The importance of being truthful with the public—Is honesty the key to reducing fear and panic to bring a community together and combat the socially-isolating nature of pandemic? [46:15]

San Francisco is an interesting case study

- They had some of the most aggressive restrictions

- There was a law that you had to wear a mask while in public

- In the end, however, SF had the forth or fifth highest mortality in the country (partly because masks didn’t really work)

- John says that SF, despite the high mortality, came away with a stronger sense of community

- And he attributes that to the fact that the leaders in SF were very honest and truthful with the people

“Telling the truth is the best way to go and that it can pull people together, even in a pandemic, people function as they do in other disasters, trying to help each other.”

Third wave of Spanish flu in the spring of 1919 [51:30]

What might explain how a third wave occurred?

- It was NOT due to seasonality, says John

- John believes the virus changed for a third time

- Neither exposure to the first wave or the second wave seemed to protect against the third wave suggesting there was an antigenic drift in the virus

- The third wave was very lethal but not quite to the severity of the second wave in 1918

Global impact of Spanish flu, a high mortality in the younger population, and why India hit so much harder than other countries [55:15]

Why did India suffer such a high mortality rate?

- Somewhere between 20-30 million people in India died

- Why?

- Not so sure

- Best guess is that they weren’t exposed to the first wave of Spanish flu and therefore weren’t provided immunity

Western day Samoa

- In an isolate

- d Island in the Pacific Western, Samoa, 22% of the entire population died

- It can probably be explained by a “naive” immune system

Global mortality

- 50 to 100 million people died

- 1.8 billion total population

- That’s means somewhere between 2.5-5% of the world population died from Spanish flu

Demographics

- Two thirds of the dead were aged 18 to 45

- 3% of the entire population of factory workers in that age group died in a period of weeks

- 6% of the entire population of miners died

- Pregnant women had the worst mortality rate somewhere between 23-71%

What happened to the economy and the mental psyche of the public in the years following the pandemic? [59:20]

The economy

- A recession occurred that was very “deep” but “short-lived”, says John

- When WW1 ended, millions of soldiers were thrust back into the workforce

- Fortunately, there was plenty of pent up demand given that many of the civilian products had been stopped in production in order to make war related products

Public psyche

- Hard to quantify the psyche, says John

- But clearly it remained in people’s consciousness

- In The Berlin Stories, Christopher Isherwood wrote that when the Navi’s rolled into Berlin in 1933, “you could feel it like influenza in your bones”

Comparing the 2009 H1N1 virus to Spanish flu [1:02:10]

The 2009 H1N1

- Oddly, it almost had 2 entirely different diseases

- The overwhelming majority of people who got sick had relatively mild case of influenza

- But for those who were seriously ill, it was basically as severe as the 1918 flu

- The 1918 was actually a H1N1 virus

- The 2009 H1N1 could bind directly to cells deep in the lung

- John can’t speak to the similarities in the genetic makeup

- But, it’s interesting to point out, just like Spanish flu of 1918, the average age of those who died in 2009 skewed much younger (avg. age was 40) compared to most influenzas

Comparing SARS-CoV-2 to the Spanish flu [1:04:20]

Main similarity: Coronavirus, similar to 1918 flu, can bind directly to the cells in lungs as well as upper respiratory

Main difference: The incubation period… this makes managing COVID a nightmare

- Influenza incubation is 2-4 days

- SARS-CoV-2 incubation is 5-6 days

- The disease (COVID-19) takes longer to develop in the body and takes much longer to pass through

- This results in the whole process being stretched out over a longer period of time compared to influenza whereas the flu passes through a community in 6-10 weeks until the next “season”

- Social distancing is a good thing… but it does sort of extend the time it takes for the virus to run its course

Do you have immunity after you recover from COVID-19?

- John says what he has seen suggests that you will have immunity for a year and maybe longer if you’ve already been exposed

What are John’s thoughts on how our government and leaders have handled the current pandemic? [1:08:00]

- John thinks the federal government has failed miserably at leading the charge on this

- The CDC did a bad job with the testing kits

- He also says he’s worried that the federal government isn’t doing enough in terms of developing an infrastructure that we will need in order to do widespread testing and contact tracing

Sweden’s herd immunity approach, and understanding case mortality rate vs. infection mortality rate [1:10:40]

- Sweden is pursuing a “herd immunity” approach while trying to protect the most vulnerable

- Sweden is basically predicting that the infection mortality rate is closer to 0.1-0.3% (like influenza) as opposed to where the case mortality rate currently resides between 1-2%

Infection mortality rate vs. case mortality rate

- Infection mortality rate means number of deaths per person who gets infected

- Case mortality rate is the number of deaths per reported case of infection

- John says the infection mortality of influenza is likely way below 0.1%

“If you did a serological study to find out how many people were infected with influenza, the influenza case mortality I’m convinced would drop from 0.1%, you know, way off the scale, way below that.”

What are some important lessons that we can apply going forward? [1:13:00]

- We need better leadership, says John

- He believes no politician should be the spokesperson

- Rather it should be someone without political affiliation

- We need to do better at managing the public’s expectations, says John

- We need to build up an infrastructure for testing and contact tracing while we are social distancing so we can get the economy back up sooner rather than later

Does John think we will be better prepared for this in the future? [1:16:00]

- John’s optimistic that there will be a significant investment in monitoring emerging diseases

- Furthermore, we’ve learned from SARS and MERS and that gives us a huge headstart on a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2

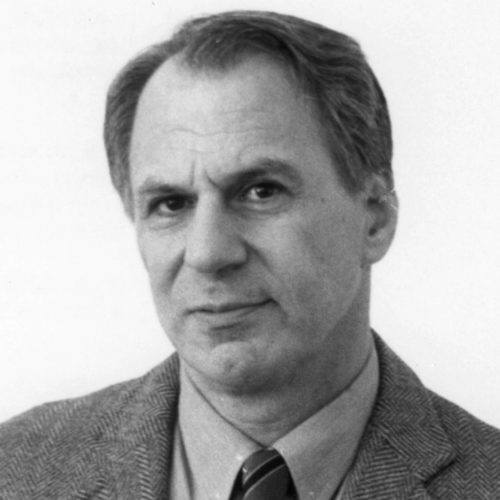

John Barry

John M. Barry is a prize-winning and New York Times best-selling author whose books have won multiple awards. The National Academies of Sciences named his 2004 book The Great Influenza: The story of the deadliest pandemic in history, a study of the 1918 pandemic, the year’s outstanding book on science or medicine. His earlier book Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America, won the Francis Parkman Prize of the Society of American Historians for the year’s best book of American history and in 2005 the New York Public Library named it one of the 50 best books in the preceding 50 years, including fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. His books have also been embraced by experts in applicable fields: in 2006 he became the only non-scientist ever to give the National Academies Abel Wolman Distinguished Lecture, a lecture which honors contributions to water-related science, and he was the only non-scientist on a federal government Infectious Disease Board of Experts. He has served on numerous boards, including ones at M.I.T’s Center for Engineering Systems Fundamentals, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the Society of American Historians. His latest book is Roger Williams and The Creation of the American Soul: Church, State, and the Birth of Liberty, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and winner of the New England Society Book Award.

His books have involved him in two areas of public policy. In 2004, he began working with the National Academies and several federal government entities on influenza preparedness and response, and he was a member of the original team which developed plans for mitigating a pandemic by using “non-pharmaceutical interventions”– i.e., public health measures to take before a vaccine becomes available. Both the Bush and Obama administrations have sought his advice on influenza preparedness and response, and he continues his activity in this area.

He has been equally active in water issues. After Hurricane Katrina, the Louisiana congressional delegation asked him to chair a bipartisan working group on flood protection, and he served on the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East, overseeing levee districts in metropolitan New Orleans, from its founding in 2007 until October 2013, as well as on the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, which is responsible for the statewide hurricane protection. Barry has worked with state, federal, United Nations, and World Health Organization officials on influenza, water-related disasters, and risk communication.

His writing has received not only formal awards but less formal recognition as well. In 2004 GQ named Rising Tide one of nine pieces of writing essential to understanding America; that list also included Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address and Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” His first book, The Ambition and the Power: A true story of Washington, was cited by The New York Times as one of the eleven best books ever written about Washington and the Congress. His second book The Transformed Cell: Unlocking the Mysteries of Cancer, coauthored with Dr. Steven Rosenberg, was published in twelve languages. And a story about football he wrote was selected for inclusion in an anthology of the best football writing of all time published in 2006 by Sports Illustrated.

A keynote speaker at such varied events as a White House Conference on the Mississippi Delta and an International Congress on Respiratory Viruses, he has also given talks in such venues as the National War College, the Council on Foreign Relations, and Harvard Business School. He is co-originator of what is now called the Bywater Institute, a Tulane University center dedicated to comprehensive river research.

His articles have appeared in such scientific journals as Nature and Journal of Infectious Disease as well as in lay publications ranging from Sports Illustrated to Politico, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Fortune, Time, Newsweek, and Esquire. A frequent guest on every broadcast network in the US, he has appeared on such shows as NBC’s Meet the Press, ABC’s World News, and NPR’s All Things Considered, and on such foreign media as the BBC and Al Jazeera. He has also served as a consultant for Sony Pictures and contributed to award-winning television documentaries.

Before becoming a writer, Barry coached football at the high school, small college, and major college levels. Currently Distinguished Scholar at Tulane’s Bywater Institute and a professor at the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, he lives in New Orleans. [johnmbarry.com]