In this “Ask Me Anything” (AMA) episode, Peter and Bob discuss all things related to GLP-1 agonists—a class of drugs that are gaining popularity for the treatment of obesity. They cover the discovery of these peptides, their physiology, and what it is they do in their natural state. Next, Peter and Bob break down a recently published study which showed remarkable results for weight loss and other metabolic parameters using a once-weekly injection of the GLP-1 agonist drug semaglutide, also known as Ozempic, in overweight and obese patients. Finally, they compare results from the semaglutide study to results from various lifestyle interventions and give their take on the potential future of GLP-1 agonists.

Below is a sneak peek of the episode. If you’re a member, you can listen to this full episode on your private RSS feed or on our website here. If you are not a member, subscribe now to gain immediate access to this full episode, our entire back catalog of AMA episodes, plus more great benefits!

We discuss:

- Remarkable results of a recent study in overweight adults [2:15];

- Key background on insulin, glucagon and the incretin effect to appreciate the effects of semaglutide [4:00];

- What is GLP-1 and how does it work? [16:30];

- 2021 semaglutide study: remarkable results, side effects, and open questions [30:00];

- Semaglutide vs. lifestyle interventions: comparing results with semaglutide vs. lifestyle interventions alone [44:00];

- Closing thoughts and open questions on the therapeutic potential of semaglutide [47:30]; and

- More.

Get Peter’s expertise in your inbox 100% free.

Sign up to receive An Introductory Guide to Longevity by Peter Attia, weekly longevity-focused articles, and new podcast announcements.

Remarkable results of a recent study in overweight adults [2:15]

This AMA centers around this paper: Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity

- The results in terms of weight reduction were “freaking remarkable”

- Questions were around this study:

- Can you go over the findings of the study?

- What are the implications?

- Do we need a drug for obesity?

- What the heck is semaglutide?

- How does it compare to other drugs and diets?

- For example, there are other drugs in this class, liraglutide, that about six years ago showed also very promising results

- But you can’t really go deep on this paper without doing a little bit of background on what GLP-1 is because this drug (semaglutide) is effectively just an analog of GLP-1

Key background on insulin, glucagon and the incretin effect to appreciate the effects of semaglutide [4:00]

This first discussion is a prologue to make sure that we understand how semaglutide works

- Looking through the lens of ‘what is an incretin?’, or ‘what is the incretin effect?’

- Only when you can measure insulin can you understand what the incretin effect is

- Effectively, it comes down to a bit of a mismatch between how oral and intravenous glucose are processed

Taking a step back…Insulin and glucagon are two hormones that you have to really understand to get what incretins are and then by extension to appreciate what semaglutide is doing

-What is insulin?

- Insulin is secreted by beta cells in the pancreas

- The pancreas has two broad functions: i) an endocrine function and ii) an exocrine function

- Exocrine function is kind of the local digestive function

- The endocrine function is the more systemic function

- The release of insulin and glucagon from beta and alpha cells respectively fit into the endocrine portion of this

- By mass, only 5% of the pancreas is really endocrine function is alpha and beta cells

- The majority of the pancreatic mass is for the exocrine, the local digestive function.

- The pancreas has two broad functions: i) an endocrine function and ii) an exocrine function

- Beta cells secrete insulin

- Insulin really has pretty significant effects on muscle cells, fat cells and liver cells

- Signals all of these tissues to take up glucose

- Also tells the liver to stop making glucose

- The purpose of insulin is a signal of the fed state and it’s particularly sensitive of course to carbohydrate

- So it’s saying when carbohydrates are abundant, we need to take glucose up into cells and we need to stop making more glucose

- One of the most important functions of the liver, in fact you could argue the function with which we would die the quickest is its ability to make glucose and put it into circulation

- It also regulates the output of glucagon

-What is glucagon?

- Glucagon is produced by alpha cells of the pancreas and it increases blood glucose via hepatic glucose production by stimulating glycogenolysis, so breaking glycogen into glucose and gluconeogenesis

- it also increases lipolysis and ketone production

- There’s a bit of an antagonistic relationship between these hormones and therefore when one goes up, it would regulate the other.

How does all this fit into the incretin effect?

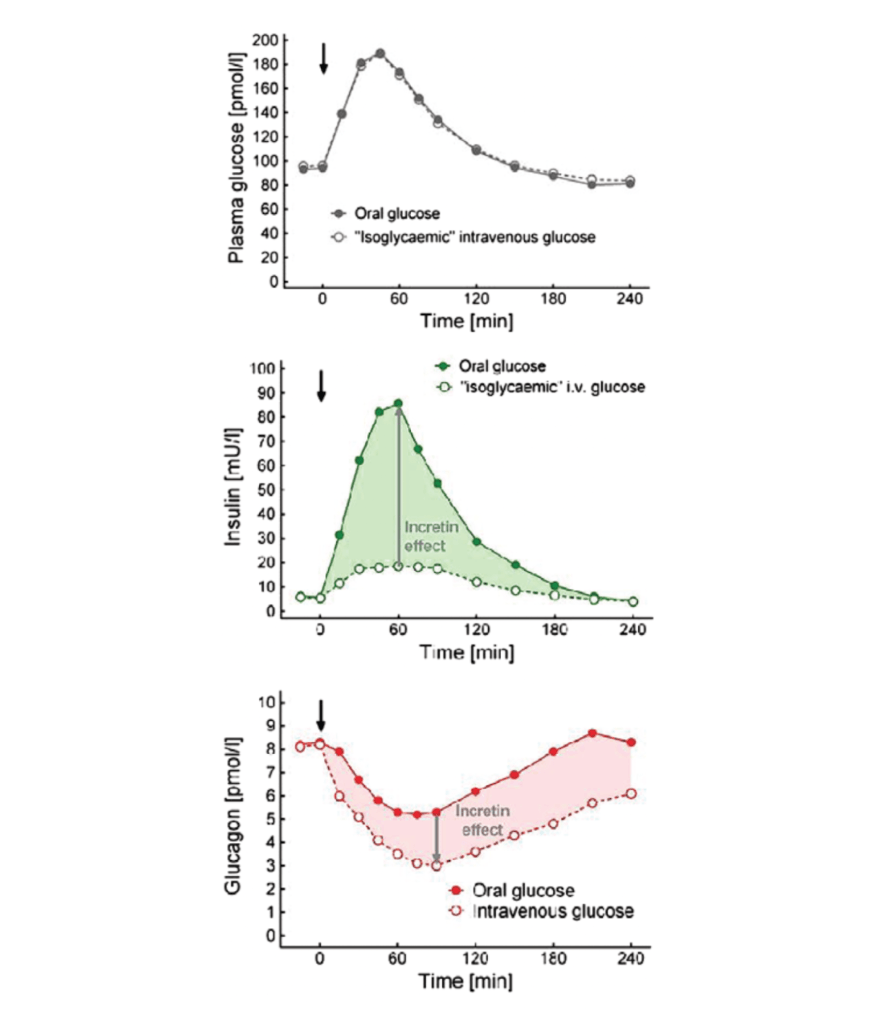

Figure 1. Contribution of the incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 to the stimulation of insulin secretion. (Nauck and Meier, 2018)

The upper graph:

- The X axis show time in minutes—as all 3 graphs do

- On the Y axis, you’re seeing plasma glucose

- This is in response to both an oral and intravenous glucose load

- in the solid gray circles is the measured plasma glucose level following a glucose load

- This is done in picomole per liter which is equivalent to milligrams per deciliter

- So you’re looking at a normal glucose say in the 90s

- Following the ingestion of oral glucose, you see it goes up, but it peaks at about 60 minutes and then by three hours it’s effectively back to baseline.

- The intravenous glucose dose is delivered in what’s called an iso-glycaemic manner—meaning the IV of glucose is titrated to match the glycemic response

The second figure (green figure),

- This shows what happens to insulin under these two conditions

- Again, we’re sampling peripheral insulin

- In the first example, you see insulin goes up

- This would be sort of what you would expect from an oral glucose tolerance test—so insulin peaks at about 90 minutes, returns to baseline in about three to four hours.

- But what’s really interesting here is when you look at the insulin response under the intravenous glucose administration, it’s a fraction of what is delivered or appreciated in the oral glucose administration

- In fact, it almost looks like a flat line

- What explains that difference?

- That difference, which is basically the shaded green area, is referred to as the incretin effect

Looking at the red graph

- You’re going to appreciate this same difference with respect to glucagon.

- In the case of the oral glucose administration, you’re seeing the solid dots—glucagon levels go down because as glucose becomes more available in the periphery, the pancreas will make less glucagon for the liver to respond to make less glucose

- Remember, glucagon is secreted by the pancreas as well and it acts primarily on the liver to regulate glucose output, glycogen breakdown, and glucose production

- And you can see with the oral glucose administration, the attenuation of glucagon is less than with the intravenous administration

- Again, that delta is referred to here as the incretin effect

So, why does this happen?

{end of show notes preview}

Would you like access to extensive show notes and references for this podcast (and more)?

Check out this post to see an example of what the substantial show notes look like. Become a member today to get access.